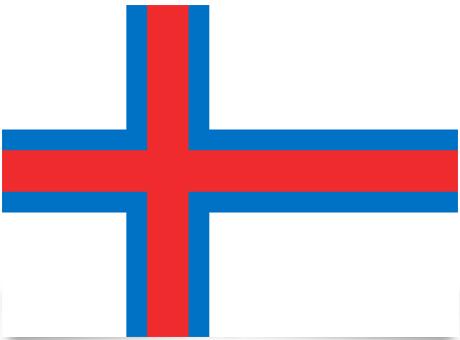

Faroe Islands Flag and Meaning

Flag of Faroe Islands

Faroe Islands Flag Meaning

The flag was first hoisted in 1919. It was semi-official from 1931 and was not officially established until 1948. The flag is designed by two Faroese students with the Icelandic flag as a model. Red and blue are the traditional colors of the islands. The cross must show the connection to the Nordic countries and common Christianity; white stands for the foam of the sea and the clean, bright sky. In 1959, the blue color changed from dark blue to azure. The flag can be used everywhere in Denmark without special permission. Ang. Weapons of the Faroe Islands, see Denmark (national coat of arms).

Faroe Islands Overview

| Population | 48,000 |

| Currency | Faroese Kr |

| Area | 1,400 km² |

| Capital city | Torshavn |

| Population density | 34.2 residents/km² |

The Faroe Islands (Føroyar) are a group of islands in the Atlantic Ocean between Shetland (distance 280 km), Iceland (430 km) and Norway (575 km), consisting of 18 islands, of which 16 are inhabited. The climate is rainy and cloudy. Due. The Gulf Stream is temperate in both winter and summer. Only 6% of the surface is cultivated. It is unsuitable for grain, so vegetables are grown instead. In all the islands there is a relatively extensive sheep breed. At Suderoy there is some mining. 20% of the population are artisans. 21% are employed in the fishing industry, which accounts for 90% of exports. As a result of the general decline in fishing, the islands have been investing in salmon farming since the 1980’s and are today among the world’s 10 largest producers. In addition, exploration has started in the sea for oil deposits.

The people: Scandinavian origin

Religion: Lutheran Protestant. There is a significant group of Baptists and a small Catholic community.

Language: Faroese.

Political parties: The Social Democracy and the Sambandspartiet (liberally) agree to maintain relations with Denmark. The leftist Republicans, the People’s Party and the Progressive Party advocate for independence.

Capital: Thorshavn, 19,000 in (2008).

Other major cities: Klaksvik 4,800 residents; Runavik 2,500 residents (2000).

Government: The slaughter has 32 members elected by proportional elections. It appoints a government – the Government – made up of 6 ministers. The team member since September 2015 is Aksel V. Johannesen. The State Ombudsman represents the Danish state and is called Lene Moyell Johansen. The Faroe Islands also elect 2 members to the Danish Folketing.

National Feast Day: Olaifest (July 29)

The Faroe Islands have been inhabited for about 1000 years. Apart from some Irish monks in the 800’s, it was Norwegians who settled. After a short period of autonomy up to 1035, the islands came under Norwegian rule; From 1380 under the Danish-Norwegian state community and later under pure Danish rule. Already in the 13th century the first sprouts developed into a trading monopoly on the islands. By 1654, this had developed so far that the Faroe Islands were granted as a loan to the Dane Christoffer Gabel and ruled as a private colony. Throughout this period, the islands were a farming community based on sheep breeding. The main exports were wool and wool articles, not least home-knit socks. Yields were tough and poverty was great.

In the late 1700’s, Poul Nolsøe – Nólsoyar Pál – emerged after 10 years abroad. He became a people hero. Not least known for his poem Fuglakvædi, in which he skin the Danes. He tried to get the Faroese to start fishing in great style. The development was slow and hesitant, but gradually created the financial basis that should allow for increased political autonomy. World War II was an economic breakthrough because the Faroese fishermen and sailors maintained the trade relationship between Britain, Iceland and the islands and saved foreign exchange reserves.

Political system

The political breakthrough took place with Jóannes Patursson (1866-1946). He was king farmer at Kirkubø – the birthplace of King Sverre. He was the great-grandson of Nólsoyar Páll, married an Icelandic woman and had studied in Norway. This helped create the basis for a strong national freedom drive. In 1901 he was elected to the Danish Parliament, and for the rest of his life he devoted himself to politics. Early on, he formulated a program that is only partially implemented today: the islands have a popular choice with far-reaching autonomy in domestic affairs, and a parliamentary responsible national government. But the islands are still part of the Danish state community – without their own foreign or defense policy. However, in January 1974 the islands decided not to join the EC.

Farmers and real estate

Until this century, the Faroe Islands were a peasant society. The land was divided into farmland and royal land. The farmland was owned and inherited by the peasants. In this way, the farms were divided into small pieces between all the siblings, and the property conditions inland are therefore quite chaotic. The royal land was state property. The land was leased, but according to tradition, a son has the right to follow his father in the contractual relationship. The land cannot be divided, which is why a king’s farmer is even better off than a farmer. The land is also divided into inland (bay) and outfield (garden). The farm is located near the houses and belongs to the villages. It is this land that is inherited and divided. Hagenis joint ownership of the whole village. It is predominantly used as a pasture for sheep. Some villages have privately owned sheep on the common pastures, but most often the sheep are jointly owned. During the harvest, the meat is distributed according to the size of the individual’s property.

These old rules for special ownership and joint ownership still apply, but have lost some of their importance as fishing has taken over the role of the dominant industry in the islands.

Language and literature

The Faroe Islands belong to the Norse language area. Despite economic exploitation and political repression on the part of Denmark, the vernacular has survived. In the 19th century it was given a fixed writing style and an accent apparatus. Over the course of a hundred years, the islands have received a wealth of literature which the numerically limited population has been able to publish in book form.

William Heinesen is probably the best known author outside the country. He writes his books in Danish. In 1975, however, Thorshavn’s only organized publisher was able to present his entire works translated into Faroese. Faroese literature opens up a greater understanding of the peculiar community. But language is also possible for understanding. For Danes, the pure Icelandic language may be difficult to access, while Faroese is closer to us and may be the key to an important part of Nordic literature.

“Development” – centralization

The Faroe Islands have been subject to structural changes to the post-war era to a greater extent than the other Nordic countries. A modern fishing fleet has led to a rapid obsolescence of the old rural community. Monetary wealth has eradicated much poverty, but at the same time has broken down the former self-sufficiency, making the country much more dependent on the outside world. Some of the islands are being depopulated; This is especially true of the Mycenaean furthest west, where 200 people lived 50 years ago – today barely 25. But overall, the population has increased significantly.

Under the natural household it was the resources that set the framework for the population. People who did not own land were not allowed to marry. Married couples had to have their own bedroom once they had allowed the 3 children allowed. “But it happened that they met on the attic”.

Over 100 years, the population has quadrupled. The basis of life still depends on good fishing. Therefore, the Faroe Islands had to fight to stay outside the EC when Denmark entered 1972. In 1977, the country expanded its fishing limit to 200 nautical miles to protect fish stocks.

The 1980’s were marked by heavy economic expansion, but in the early 1990’s the country was plunged into a deep economic crisis, quickly gaining political overtones. The Danish Bank’s branch in the Faroe Islands suffered heavy losses as a result of the crisis, and these losses were left to the Faroe Islands when the bank parted with its branch. In the late 1990’s, the Faroe Bank scandal led to increased demands for Faroese autonomy and a strengthening of the left.

The association group Kaj Leo Johannesen became a layman in 2008, in September 2011 he printed elections that were held in October. Both his own and the other large bourgeois party progressed, while the Social Democracy and the Left declined.

In February 2014, the slaughter decided to build two new tunnels between the islands. One was to go between Streymoy and Eysturoy (Eysturoyartunnilin) and the other between Streymoy and Sandoy (Sandoyartunnilin). They expected completion by 2021.

In 2014, a wind farm was put into operation near Thorshavn. It produced 12MW and saved the country for annual imports of 8,000 tonnes of oil. In October 2016, a 700KWh Lithium Ion battery was put into operation, which helped to stabilize the electricity supply. However, hydropower accounted for 39.5% of total consumption, but still accounted for a larger proportion of electricity generation. Wind energy accounted for 11.3%.

In the 2015 parliamentary elections, the Social Democracy went up 2 seats to 8, while the Republicans went 1 up to 7. The People’s Party and the Unionist Party each went back to 6 seats.